Ice on the airway

We left the KBMG airport around 3:30 headed for home, KJGG. During our Lancair test drive an hour earlier we saw that the clouds were from about 8,000' to 10,000'.

Our trip back was planned for 9,000 but we requested 11,000 right away, since we wanted to get "on top". We took off and pointed ourselves eastward, on the direct course we had been cleared for. Climbing out we felt a few bumps as we entered one or two clouds, but it was looking good that 11,000 would get us on top.

It took a while to get cleared to that level, since we had to be handed off to Indy Center at 10,000'. By the time we were cleared to that height, we were entering some building clouds – their tops were starting to get into the 12,000' or higher range. We asked for 12,000' and were cleared for that, but soon we were entering a cloud with major updrafts in it. The ride was bumpy and maintaining altitude became a bit of a chore. Since the pilot needs to be using oxygen at 12,500' we couldn't climb any higher.

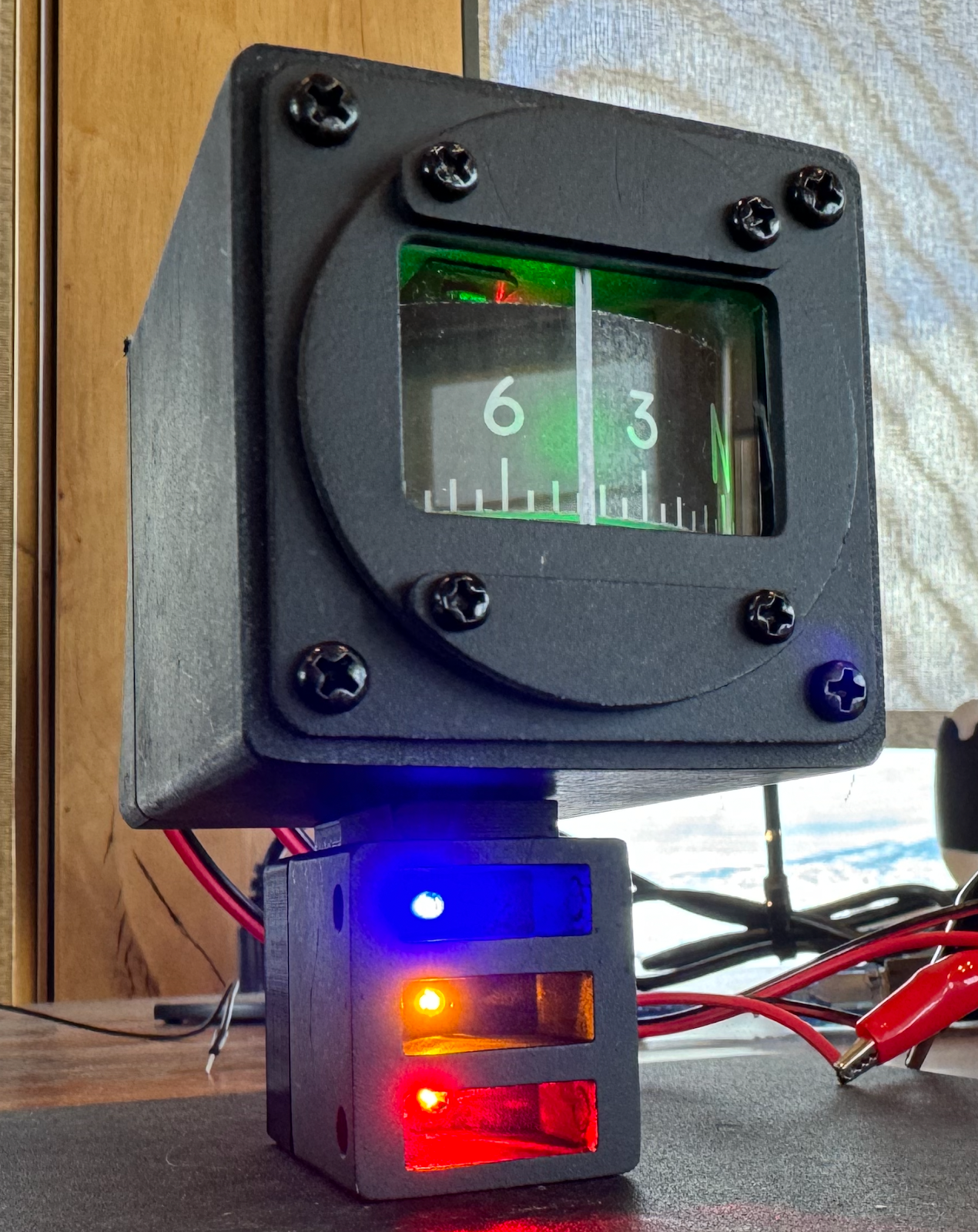

Soon however we hear (and saw) liquid rain pelting us. We all looked right to the OAT – outside air temp – sensor readout to see what the icing possibility was. The OAT was showing -1C so we all immediately started watching the wings. Jim had preemptively turned on the anti-icing that his SR22 provides – it is a weeping-wing design where low-freezing-point liquid is oozed out of laser drilled holes on the leading edge of the wing and horizontal stabilizers as well as on the prop and windshield. He turned it from NORM mode to MAX mode, which puts twice as much anti-ice fluid out. Here's a picture of the system - it's the grey shine on the leading edge of the wing:

We watched the wingtips start to gather rime ice – jagged looking ice – and decided we didn't want to stick around to see if much of that started collecting on the rest of the wing. We were also getting knocked around a lot by the thermals so Jim asked for a lower altitude. We knew it was warmer below so that made sense as an ice escape plan. Indy Center cleared us to descend at pilot's discretion once we told them about the ice and Jim nosed the airplane down.

I'm in the back seat with John and I look over at him. He's holding up the number 1 on his left hand and the number 3 on his right. I give him a quizzical look. Then he holds up 1 on the left and 4 on the right. I'm still not getting it. He points to the altimeter. I lean right enough to see it is showing 14,000. I take a bit of a deep breath pulling in a little more of the thin air than usual. I lean back into my seat and John's now holding up 1-5. Another glance shows me that we have now been pushed up to 15,000' and are still climbing.

At that point, seeing that the updrafts are not letting us go down in the least bit, Jim drops the throttle back even more and we start to finally lose a little altitude. A few long seconds later and we are out of the worst of the thermals and get down to 9,000' quickly. I take another deep breath.

We keep battling the ice for a bit more but never do pick up too much on the main portion of the wing. The TKS anti-ice is doing its job nicely and I am happy to see liquid water flowing quickly down the back of the wing and over the flaps – not turning solid. Much better than what can happen if you don't get the TKS system on nice and early (or in more extreme icing conditions).

We drive through another shower or two and had to deviate a good bit around the larger clouds. Mike passed along a tip that if you tell the controller you'd like to "deviate to the east" instead of "turn 15 degrees left" you can just get back on course once you've past the weather without having to get cleared back. The controllers always approved the requests and just asked us to report "back on course".

I turned on the iPod when we were in mostly clear weather again to get some relaxing jazz going through the headsets.

We ended the flight with a nice touchdown. While the Cirrus backseat is fairly comfortable, I was certainly ready to get out and stretch.

--------

I learned a lot about IFR travel today. Building, sharp (non-fuzzy) clouds mean turbulence. Ice is not to be messed with. We had an out during the flight, even without the TKS system, and that was to descend into the warmer air we knew was below us. Having a dependable "out" is critical - whether you're on the highway driving or in the sky flying.

Our trip back was planned for 9,000 but we requested 11,000 right away, since we wanted to get "on top". We took off and pointed ourselves eastward, on the direct course we had been cleared for. Climbing out we felt a few bumps as we entered one or two clouds, but it was looking good that 11,000 would get us on top.

It took a while to get cleared to that level, since we had to be handed off to Indy Center at 10,000'. By the time we were cleared to that height, we were entering some building clouds – their tops were starting to get into the 12,000' or higher range. We asked for 12,000' and were cleared for that, but soon we were entering a cloud with major updrafts in it. The ride was bumpy and maintaining altitude became a bit of a chore. Since the pilot needs to be using oxygen at 12,500' we couldn't climb any higher.

Soon however we hear (and saw) liquid rain pelting us. We all looked right to the OAT – outside air temp – sensor readout to see what the icing possibility was. The OAT was showing -1C so we all immediately started watching the wings. Jim had preemptively turned on the anti-icing that his SR22 provides – it is a weeping-wing design where low-freezing-point liquid is oozed out of laser drilled holes on the leading edge of the wing and horizontal stabilizers as well as on the prop and windshield. He turned it from NORM mode to MAX mode, which puts twice as much anti-ice fluid out. Here's a picture of the system - it's the grey shine on the leading edge of the wing:

We watched the wingtips start to gather rime ice – jagged looking ice – and decided we didn't want to stick around to see if much of that started collecting on the rest of the wing. We were also getting knocked around a lot by the thermals so Jim asked for a lower altitude. We knew it was warmer below so that made sense as an ice escape plan. Indy Center cleared us to descend at pilot's discretion once we told them about the ice and Jim nosed the airplane down.

I'm in the back seat with John and I look over at him. He's holding up the number 1 on his left hand and the number 3 on his right. I give him a quizzical look. Then he holds up 1 on the left and 4 on the right. I'm still not getting it. He points to the altimeter. I lean right enough to see it is showing 14,000. I take a bit of a deep breath pulling in a little more of the thin air than usual. I lean back into my seat and John's now holding up 1-5. Another glance shows me that we have now been pushed up to 15,000' and are still climbing.

At that point, seeing that the updrafts are not letting us go down in the least bit, Jim drops the throttle back even more and we start to finally lose a little altitude. A few long seconds later and we are out of the worst of the thermals and get down to 9,000' quickly. I take another deep breath.

We keep battling the ice for a bit more but never do pick up too much on the main portion of the wing. The TKS anti-ice is doing its job nicely and I am happy to see liquid water flowing quickly down the back of the wing and over the flaps – not turning solid. Much better than what can happen if you don't get the TKS system on nice and early (or in more extreme icing conditions).

We drive through another shower or two and had to deviate a good bit around the larger clouds. Mike passed along a tip that if you tell the controller you'd like to "deviate to the east" instead of "turn 15 degrees left" you can just get back on course once you've past the weather without having to get cleared back. The controllers always approved the requests and just asked us to report "back on course".

I turned on the iPod when we were in mostly clear weather again to get some relaxing jazz going through the headsets.

We ended the flight with a nice touchdown. While the Cirrus backseat is fairly comfortable, I was certainly ready to get out and stretch.

--------

I learned a lot about IFR travel today. Building, sharp (non-fuzzy) clouds mean turbulence. Ice is not to be messed with. We had an out during the flight, even without the TKS system, and that was to descend into the warmer air we knew was below us. Having a dependable "out" is critical - whether you're on the highway driving or in the sky flying.