3 hours to Indiana

Early this morning we took off in Jim's Cirrus SR22 to check out a Lancair Super ES in Bloomington, IN. John, Mike, Jim and I were airborne around 7:30AM and headed to KHTS for a refuel stop (we were fully loaded with 4 guys in the plane and had to fight a headwind).

After getting the "local's price" for gas (Jim's folks live nearby) I took the front right seat for the leg to KBMG. Mike flew left seat and did a great job of coaching me through the taxi, takeoff, cruise, and landing. We all learned a lot about the Garmin 430s from Mike. And the flight renewed my appreciation for the Cirrus - it is a roomy, comfortable, stable platform and easy to land (the trick seems to be "stay on top of the airspeeds during the approach" - not unlike many airplanes).

After getting the "local's price" for gas (Jim's folks live nearby) I took the front right seat for the leg to KBMG. Mike flew left seat and did a great job of coaching me through the taxi, takeoff, cruise, and landing. We all learned a lot about the Garmin 430s from Mike. And the flight renewed my appreciation for the Cirrus - it is a roomy, comfortable, stable platform and easy to land (the trick seems to be "stay on top of the airspeeds during the approach" - not unlike many airplanes).

Arriving into KBMG we taxied to parking and saw the Lancair Super ES on the ramp.

The Super ES is and kit-built airplane provided by Lancair International Inc. You start with the kit (which includes the major components such as the fuselage and wing pre-built) for about $80k. Then you buy the engine and prop (another $50K) as well as the avionics, lights, fuel system, etc. The price is likely to get up to about $200k when it's all said and done, but that's not factoring in the time required to actually build it.

The Super ES is and kit-built airplane provided by Lancair International Inc. You start with the kit (which includes the major components such as the fuselage and wing pre-built) for about $80k. Then you buy the engine and prop (another $50K) as well as the avionics, lights, fuel system, etc. The price is likely to get up to about $200k when it's all said and done, but that's not factoring in the time required to actually build it.

Lancair offers programs to help you build the airplane while still ensuring that you, the owner, build at least 51% of the plane (as per FAA reqs). My guess is that the factory build assist would be the way to go as they would not only offer you the space and tools you'd need but also the know-how and organization required. Organization is not something to be overlooked on a build like the ES. In fact, Glasair found that weekend builders of their aircraft spent ~80% of their time looking for parts in the kit, finding tools, or simply getting room to work - time spent not actually building anything.

If you go with the 310hp engine, then your ES is called "Super ES". Go with the 200hp engine and you only go by the name "ES". They also offer a pressurized version of the airplane allowing you to throw in a turbocharged engine and spend your time flying in the higher altitudes, hopefully over the weather. That version goes by the name of "ES-P" - you can guess what the "P" stands for.

I've had off-and-on daydreams about building my own airplane for quite a while and my limited research has put the Super ES at the top of the list. I was excited to see one in person to get a real feel for it. The design of the ES was the parent of what would eventually become the Columbia 300/350/400 but as I was to find out, they are certainly different airplanes.

After meeting the sales broker we all started walking around the Lancair getting a good look at it. Over the FBO speaker we heard another Lancair coming in to land. John had contacted an expert Super ES build, Jim Scales, to see if he would meet up with us to look over the airplane and offer his thoughts. Jim has received high praises (as well as multiple awards) for his personal Super ES and we found them all to be well founded. Another builder has a page devoted to some info on Jim Scales' Super ES.

The first thing that stood out about the design of the ES is the tall landing gear and narrow width between the main gear. Mike pointed out that - compared to the Cirrus’ low, wide stance - taxiing could be tricky in windy conditions.

We all walked around the machine, admiring the curves in the composite surfaces. Composite aircraft (which most new designs utilize) all have super smooth surfaces – nice for cutting down drag. Add a little wax on top and they are a slick as ice. The difference is very obvious in a side-by-side comparison. Next time you’re at the airport, check out how the light bounces off of a 172 vs. a Diamond or a Cirrus. The latter craft will look like a mirror where the 172’s skin will look very wavy and bumpy from the aluminum and the many rivets.

Climbing into the cockpit the first issue we noticed was that getting up on the high wing was tricky. This was not helped by the fact that there was no handhold to use for steadying.

We found that the best way, though not ideal, was to open the door and reach way up to grab the back edge of the door opening.

Once sitting in the cockpit, which required a bit of contortion (not good for inflexible folks), a big problem became immediately apparent. The cockpit is not designed for a tall person. My relatively long legs were jammed up against the bottom of the panel when I moved the seat close enough to reach the radios. I also had to sit twisted slightly left to avoid bending the throttle in the lower middle of the panel.

When two of us sat up front there were also issues with shoulder room. We had to overlay arms in order to fit side-by-side – not good for any significant length flight. The back seat was unique in this particular airplane. The builder basically made it into a storage area by making the seat cushion very deep (maybe twice normal depth) and constructing it to lift up to reveal storage space. This effectively made the airplane a two seater. Even though there were seat belts in the back, no one could sit there for two reasons – zero leg room and a seat front that was way too far from the seat back.

When two of us sat up front there were also issues with shoulder room. We had to overlay arms in order to fit side-by-side – not good for any significant length flight. The back seat was unique in this particular airplane. The builder basically made it into a storage area by making the seat cushion very deep (maybe twice normal depth) and constructing it to lift up to reveal storage space. This effectively made the airplane a two seater. Even though there were seat belts in the back, no one could sit there for two reasons – zero leg room and a seat front that was way too far from the seat back.

With that information in hand, John quickly decided that the airplane would not work – it was not a cross-country, family-hauling type of machine (unless your family consists of 2 smallish people).

With that information in hand, John quickly decided that the airplane would not work – it was not a cross-country, family-hauling type of machine (unless your family consists of 2 smallish people).

With that decision made, we spent the rest of our time at KBMG chatting with Jim Scales, getting a ride in his Lancair (where the back seat was quite usable), and taking him up in the SR22.

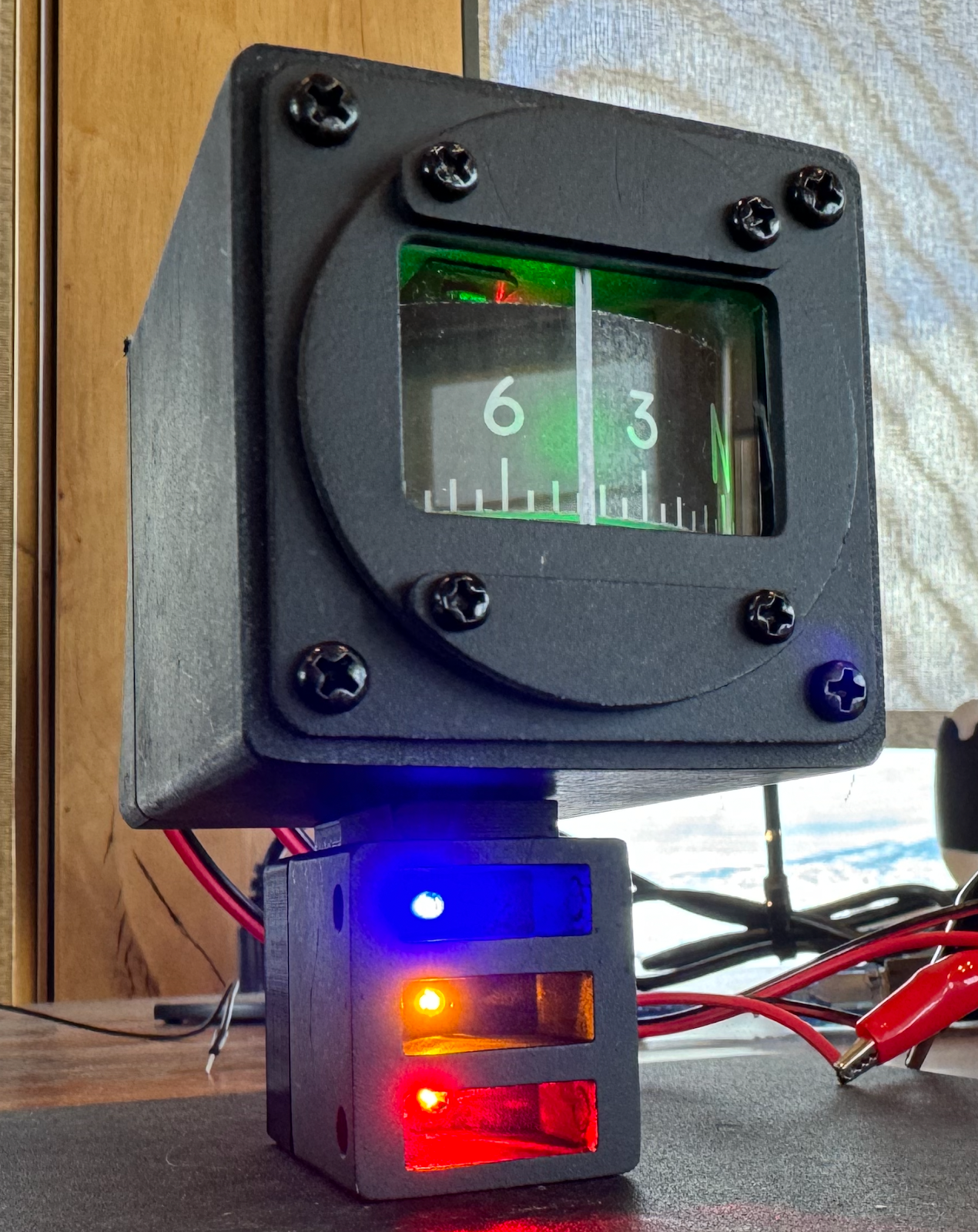

To get an idea of the high quality of Jim’s airplane’s construction, take a look at these shots of his airplane:

And compare to the other plane:

And compare to the other plane:

Don’t get me wrong - the other plane was quite nice - especially on the outside, but that last bit of polishing/finishing (maybe the final 5% of work) that looks so nice on Jim’s plane is lacking on the other.

Don’t get me wrong - the other plane was quite nice - especially on the outside, but that last bit of polishing/finishing (maybe the final 5% of work) that looks so nice on Jim’s plane is lacking on the other.

So by late afternoon we were all piling back into the Cirrus to head home. The flight back was educational enough to warrant its own post, so I will save that for later.

Things I learned on this trip:

After getting the "local's price" for gas (Jim's folks live nearby) I took the front right seat for the leg to KBMG. Mike flew left seat and did a great job of coaching me through the taxi, takeoff, cruise, and landing. We all learned a lot about the Garmin 430s from Mike. And the flight renewed my appreciation for the Cirrus - it is a roomy, comfortable, stable platform and easy to land (the trick seems to be "stay on top of the airspeeds during the approach" - not unlike many airplanes).

After getting the "local's price" for gas (Jim's folks live nearby) I took the front right seat for the leg to KBMG. Mike flew left seat and did a great job of coaching me through the taxi, takeoff, cruise, and landing. We all learned a lot about the Garmin 430s from Mike. And the flight renewed my appreciation for the Cirrus - it is a roomy, comfortable, stable platform and easy to land (the trick seems to be "stay on top of the airspeeds during the approach" - not unlike many airplanes).Arriving into KBMG we taxied to parking and saw the Lancair Super ES on the ramp.

The Super ES is and kit-built airplane provided by Lancair International Inc. You start with the kit (which includes the major components such as the fuselage and wing pre-built) for about $80k. Then you buy the engine and prop (another $50K) as well as the avionics, lights, fuel system, etc. The price is likely to get up to about $200k when it's all said and done, but that's not factoring in the time required to actually build it.

The Super ES is and kit-built airplane provided by Lancair International Inc. You start with the kit (which includes the major components such as the fuselage and wing pre-built) for about $80k. Then you buy the engine and prop (another $50K) as well as the avionics, lights, fuel system, etc. The price is likely to get up to about $200k when it's all said and done, but that's not factoring in the time required to actually build it.Lancair offers programs to help you build the airplane while still ensuring that you, the owner, build at least 51% of the plane (as per FAA reqs). My guess is that the factory build assist would be the way to go as they would not only offer you the space and tools you'd need but also the know-how and organization required. Organization is not something to be overlooked on a build like the ES. In fact, Glasair found that weekend builders of their aircraft spent ~80% of their time looking for parts in the kit, finding tools, or simply getting room to work - time spent not actually building anything.

If you go with the 310hp engine, then your ES is called "Super ES". Go with the 200hp engine and you only go by the name "ES". They also offer a pressurized version of the airplane allowing you to throw in a turbocharged engine and spend your time flying in the higher altitudes, hopefully over the weather. That version goes by the name of "ES-P" - you can guess what the "P" stands for.

I've had off-and-on daydreams about building my own airplane for quite a while and my limited research has put the Super ES at the top of the list. I was excited to see one in person to get a real feel for it. The design of the ES was the parent of what would eventually become the Columbia 300/350/400 but as I was to find out, they are certainly different airplanes.

After meeting the sales broker we all started walking around the Lancair getting a good look at it. Over the FBO speaker we heard another Lancair coming in to land. John had contacted an expert Super ES build, Jim Scales, to see if he would meet up with us to look over the airplane and offer his thoughts. Jim has received high praises (as well as multiple awards) for his personal Super ES and we found them all to be well founded. Another builder has a page devoted to some info on Jim Scales' Super ES.

The first thing that stood out about the design of the ES is the tall landing gear and narrow width between the main gear. Mike pointed out that - compared to the Cirrus’ low, wide stance - taxiing could be tricky in windy conditions.

We all walked around the machine, admiring the curves in the composite surfaces. Composite aircraft (which most new designs utilize) all have super smooth surfaces – nice for cutting down drag. Add a little wax on top and they are a slick as ice. The difference is very obvious in a side-by-side comparison. Next time you’re at the airport, check out how the light bounces off of a 172 vs. a Diamond or a Cirrus. The latter craft will look like a mirror where the 172’s skin will look very wavy and bumpy from the aluminum and the many rivets.

Climbing into the cockpit the first issue we noticed was that getting up on the high wing was tricky. This was not helped by the fact that there was no handhold to use for steadying.

We found that the best way, though not ideal, was to open the door and reach way up to grab the back edge of the door opening.

Once sitting in the cockpit, which required a bit of contortion (not good for inflexible folks), a big problem became immediately apparent. The cockpit is not designed for a tall person. My relatively long legs were jammed up against the bottom of the panel when I moved the seat close enough to reach the radios. I also had to sit twisted slightly left to avoid bending the throttle in the lower middle of the panel.

When two of us sat up front there were also issues with shoulder room. We had to overlay arms in order to fit side-by-side – not good for any significant length flight. The back seat was unique in this particular airplane. The builder basically made it into a storage area by making the seat cushion very deep (maybe twice normal depth) and constructing it to lift up to reveal storage space. This effectively made the airplane a two seater. Even though there were seat belts in the back, no one could sit there for two reasons – zero leg room and a seat front that was way too far from the seat back.

When two of us sat up front there were also issues with shoulder room. We had to overlay arms in order to fit side-by-side – not good for any significant length flight. The back seat was unique in this particular airplane. The builder basically made it into a storage area by making the seat cushion very deep (maybe twice normal depth) and constructing it to lift up to reveal storage space. This effectively made the airplane a two seater. Even though there were seat belts in the back, no one could sit there for two reasons – zero leg room and a seat front that was way too far from the seat back. With that information in hand, John quickly decided that the airplane would not work – it was not a cross-country, family-hauling type of machine (unless your family consists of 2 smallish people).

With that information in hand, John quickly decided that the airplane would not work – it was not a cross-country, family-hauling type of machine (unless your family consists of 2 smallish people).With that decision made, we spent the rest of our time at KBMG chatting with Jim Scales, getting a ride in his Lancair (where the back seat was quite usable), and taking him up in the SR22.

To get an idea of the high quality of Jim’s airplane’s construction, take a look at these shots of his airplane:

And compare to the other plane:

And compare to the other plane: Don’t get me wrong - the other plane was quite nice - especially on the outside, but that last bit of polishing/finishing (maybe the final 5% of work) that looks so nice on Jim’s plane is lacking on the other.

Don’t get me wrong - the other plane was quite nice - especially on the outside, but that last bit of polishing/finishing (maybe the final 5% of work) that looks so nice on Jim’s plane is lacking on the other.So by late afternoon we were all piling back into the Cirrus to head home. The flight back was educational enough to warrant its own post, so I will save that for later.

Things I learned on this trip:

- The Cirrus is a nice machine – roomy and easy/fun to fly (though that 310hp does give your right leg a workout)

- Tons about the Garmin 430

- I can use my VFR-only GPS for direct enroute IFR navigation if I hint to the controller, via flight plan remarks, that I have it on board. I do need to stay in radar coverage to do that though.

- Almost all experimental airplanes are short on space in the cockpit

- I doubt I will build an ES myself - it lacks the space I'd need - unlike its cousins, the Columbias, which were plenty comfortable for me

- The many features of the Garmin GPSMap 396/496 for in cockpit weather – very impressive. In fact, I was surprised by how impressive it was - way beyond what I had imagined from just reading about it.